Treatise on Rhythm, Color, and Birdsong

Contributors: Jaewook Lee, Sarah Demeuse, Aaron Schuster, Goeun Song

Translator: Daewoong Ahn

Copy Editor: Hovey Brock, Sanghoon Kang

Design: Everyday Practice

Distribution: Space O'NewWall, Seoul Museum of Art

Publisher: O'NewWall Publications

Support: Seoul Museum of Art's Emerging Artists and curators Program

Copyright @ 2016 by O'NewWall Publication

Published on 9/3/2016

ISBN: 979-11-950642-9-8

TREATISE ON RHYTHM, COLOR, AND BIRDSONG

Contributor: Jaewook Lee, Sarah Demeuse, Aaron Schuster, Goeun Song

Publisher: O'NewWall Publications

Copyright @ 2016 by O'NewWall Publication

Published on 9/3/2016

ISBN: 979-11-950642-9-8

Excerpts from Treatise on Rhythm, Color, and Birdsong

By Jaewook Lee

The present retroactively creates its necessity from the past, because the past belongs to the present’s constant reconstitution and reinterpretation in search of meanings. "How is this circle of changing the past possible without recourse to time travel? The solution was already proposed by Henri Bergson: of course one cannot change the past reality, but what one can change is the virtual dimension of the past – when something radically New emerges, this New retroactively creates its own possibility, its own causes or conditions. A potentiality can be inserted into (or withdrawn from) past reality." – Slavoj Žižek (Absolute Recoil, p. 190) The present retroactively creates its necessity from the past, because the past belongs to the present’s constant reconstitution and reinterpretation in search of meanings. Our search of meaning not only creates new reality but also retroactively designates its conditions. For example, Other Primary Structures was a recent exhibition at the Jewish Museum in New York City in 2014, which revisited their historical 1966 exhibition Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors. The 1966 show surveyed the works of Minimalist artists such as Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Walter De Maria, and others. Almost half a century later, Other Primary Structures presented works by renowned and lesser-known artists of the 60s from Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. These international artists also sought extreme formal reductions, but from a multitude of diverse perspectives. In this sense, Other Primary Structures has altered and expanded the discourse of art history by incorporating a more global scope. The recent extensive globalization of the art world has pushed art history to re-designate its conditions more broadly. As with Other Primary Structures, the task of this series of essays is to reconsider artists and creative practitioners in other fields who have been underrepresented in the art history canon not because they are less important, but because the hegemonic historical narrative has marginalized them. It is, therefore, introducing a new vantage point and set of implied relationships that bring new significance to the belittled actors of the world in the new epochal dispensation of the 21st century.

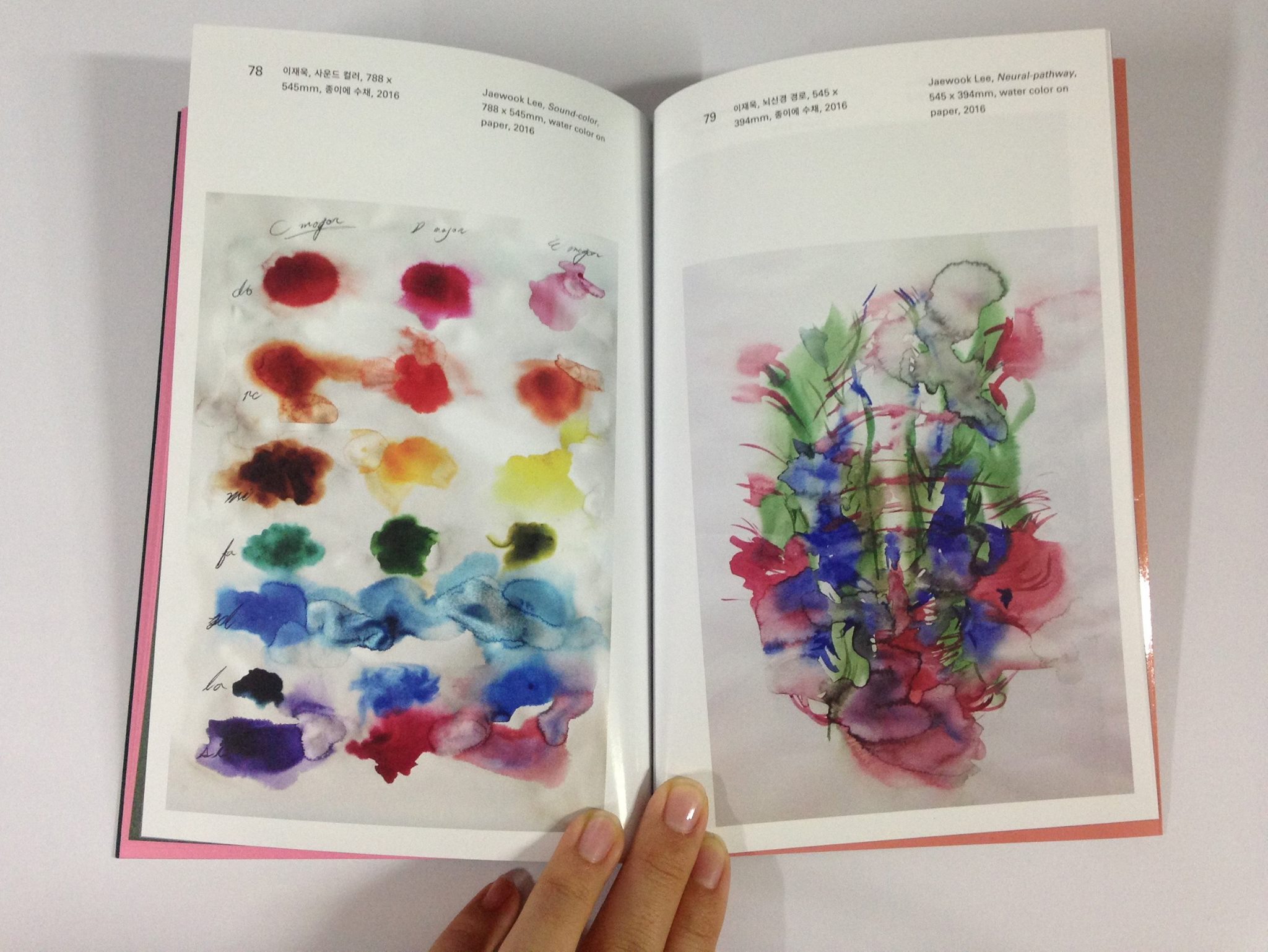

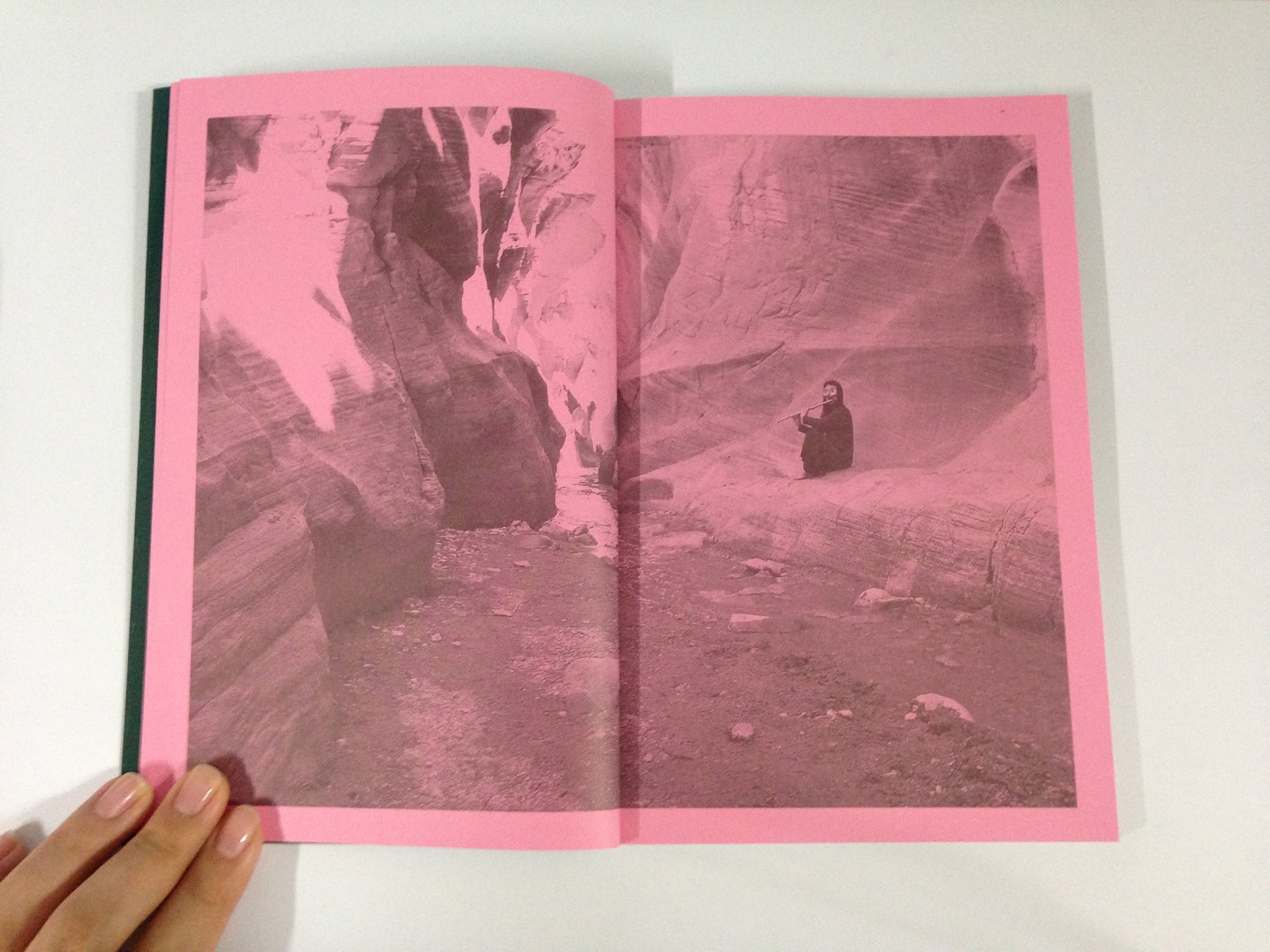

The title of this essay series is Treatise on Rhythm, Color, and Birdsong, which borrows from the title of composer Olivier Messiaen’s seven volumes of music theory, Treatise On Rhythm, Color And Ornithology. Messiaen is one of the revolutionary composers of the 20th century, and his treatise describes the theory for his compositions, how he incorporated birdsong, the relationship between sound and colors, and new scientific ideas of his time that relate to his conception of rhythms and time. The composer fearlessly sought resources from other fields of knowledge, creating different nodes of connection with the world beyond the grand narrative of music history. As is the case with Messiaen’s approach, this essay attempts a new vision of the world as a node of connections among seemingly disparate fields of knowledge, retroactively creating more open conditions by incorporating other actors of the world from the past.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, scientific revolutions, such as general relativity, quantum mechanics, and new discoveries in neurobiology, have dramatically changed our view of the world. What seemingly made sense in the past does not make sense any more. For example, according to Albert Einstein’s general relativity, our foot is slightly younger than our head because our foot is closer to the higher gravity: time flows slower below than above. Time and space are not static, but rather flexible. In quantum physics, the laws defy common sense and extend our minds to the limit. Two subatomic particles can interact with each outside of space and time. This phenomenon is known as quantum entanglement, to which Einstein famously referred as “a spooky action at a distance.” One subatomic particle can be in multiple locations at the same time. These strange rules of contemporary physics stretch the minds of scientists and artists alike, and blur the boundary between the rational and the mythical. The more we know about Nature, the more we know what we don’t know. The radical post-Newtonian world inspired a few artists in the 20th century. They tuned into to a new frequency, as it were, still faint and unheard by most, and entered into a reciprocal relationship with this strange new world in which they tried to affect it as much as it was affecting them. ....see the entire article in the print version of Treatise on Rhythm, Color, and Birdsong